|

|||

The Modern Maya - A Culture in Transition R. Jon McGee |

|||

|

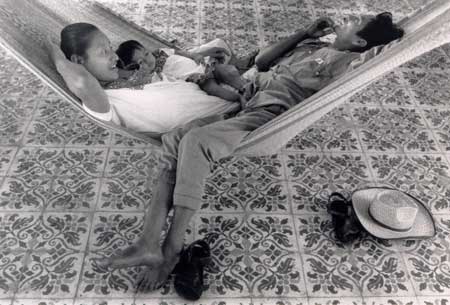

Curiously, this book opens with an introduction by Ulrich Keller that insults its principal audience. Keller states that, because Everton is a photographer and not an anthropologist, he is able to relate to his subjects "as people, as friends, rather than as anthropological subjects, i.e., objects" (pg 15). Regardless, anthropologists will enjoy the book. Everton's commentary and accompanying photographs are a superb ethnographic record of several Yucatecan Maya families over a span of 23 years. Compared to other groups, surprisingly little ethnographic effort has been expended on the Maya of the Yucatán. Most anthropological work in this area has been in archaeology. Everton's book helps remedy this situation. Working in a photo-essay format, he presents descriptions of Maya families from a variety of backgrounds, such as milperos, chicle gathers, and workers in a henequen cooperative. The lives of these families are followed from 1967 to 1990, a long-term approach rarely seen in more formal ethnographic work. A long and unfocused introduction is followed by a concise historical overview of Maya history that describes pre-Columbian Maya culture and illustrates several links between ancient and contemporary practices. The six chapters forming the main body of the book are composed of Everton's skillfully integrated photographs and observations, which provide detailed, thought-provoking, ethnographic descriptions of people who he knows and loves. Ethnographers can often be dry, but Everton's depictions of Maya life are accurate and full of feeling. Having spent much time in Mayan homes myself, his accounts made me homesick for their company. An outstanding feature of this book is its treatment of controversial political and economic issues on a human rather than an abstract level. Everton, in his account of chicle gatherers, shows readers the adversity faced by a family living under the system of debt-peonage. In a chapter on Mayan ranch hands, he presents the issue of deforestation from the point of view of a man who must make a living clearing land for an absentee landlord who raises cattle. Focusing on a henequen worker, he illustrates the difficulties faced by those who spend their lives working in export industries and the hardships caused by the decline of the world market's demand for their products. Finally, the effect of the burgeoning tourist industry in Quintana Roo is examined from the point of view of the Cruzob - Maya who moved into the forests of Quintana Roo to escape the influence of outsiders, only to find themselves overrun by the Caribbean tourist industry. Although Everton never condemns the Ruta Maya, one of the recent trends in "eco-tourism," his family histories illustrate how tourism affects the area's indigenous peoples. Everton's book is purely descriptive and does not attempt any deeper

anthropological analysis. However, this approach is the strength of

his work. He relates not only what he saw, but also what the families

he lived with had to say about their lives. Additionally, his photographs

provide a wealth of ethnographic detail, and some have tremendous emotional

impact. The book is a superb example of how photographs and commentary

should be integrated into ethnographic descriptions. Everton also broaches

issues essential to any anthropological discussion of indigenous peoples,

such as the effects of industrialization, economic exploitation, and

tourism on traditional lifestyles. However, rather than preaching his

own views on these matters, he lets the course of his Maya subjects'

lives show how these factors affect them.

|

|||